Mitigating effects of telehealth uptake on disparities in maternal care access, quality, outcomes, and expenditures during the COVID-19 pandemic

Principal Investigator

Peiyin Hung

Associate Professor, Department of Health Services Policy and Management, University of South Carolina

Principal Investigator

Xiaoming Li

Professor, Department of Health Promotion, Education, and Behavior, University of South Carolina

Co-Investigators

- Nansi Boghossian, Associate Professor, Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, University of South Carolina

- Berry Cambell, Associate Professor, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of South Carolina

- Bo Cai, Professor, Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, University of South Carolina

- Sayward Harrison, Associate Professor, Department of Psychology, University of South Carolina

- Chen Liang, Assistant Professor, Department of Health Services Policy and Management, University of South Carolina

- Jihong Liu, Professor, Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, University of South Carolina

- Cassie Odahowski, Research Associate, Rural and Minority Health Research Center, University of South Carolina

- Jiani Yu, Assistant Professor, Department of Population Health Sciences, Weill Cornell Medical College

Funded By

Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD)

The problem:

Prior to the pandemic, access to maternal healthcare varied significantly by race, ethnicity, and residence. These prenatal access issues persisted and worsened during the pandemic. For example, one in five Black women did not receive adequate prenatal care in 2020 compared to only one in ten White women. In the United States, 1,119 counties are considered maternity care deserts, and 373 counties are considered low-access areas.

Telehealth expansion, however, represented an opportunity to improve access and quality of maternity care and longer-term maternal health outcomes. The researchers aimed to answer if telehealth uptake mitigated pandemic effects on prenatal care access in the United States.

The approach:

Hung and colleagues analyzed 349,682 pregnancies from people ages 15-49 who gave birth between June 1, 2018 and May 31, 2022. Using electronic health records, the team tracked gestational week at the onset of prenatal care. Based on the timing of when the person became pregnant and the onset of the COVID-19 public health emergency, they divided pregnancies into three groups: 1) not overlapping, 2) partially overlapping, or 3) fully overlapping the pandemic period.

The researchers then analyzed trends in telehealth use for prenatal care and associations between prenatal telehealth uptake and timing of the prenatal care, as well as its variations by maternal race and ethnicity, and residence.

The findings:

A higher portion of birthing people who used telehealth received prenatal care in their first trimester compared with birthing people not using telehealth. This was particularly evident for people who were pregnant during the pandemic, suggesting that telehealth was a useful strategy to increase access to timely prenatal care in such times.

Prenatal care was initiated in the first trimester for 70 percent of non-overlapping (pre-pandemic) pregnancies and 63 percent of partially overlapping pregnancies. For pregnancies that fully overlapped the pandemic, 60 percent of birthing people who did not use telehealth initiated prenatal care in the first trimester, compared to 76 percent of birthing people who used telehealth.

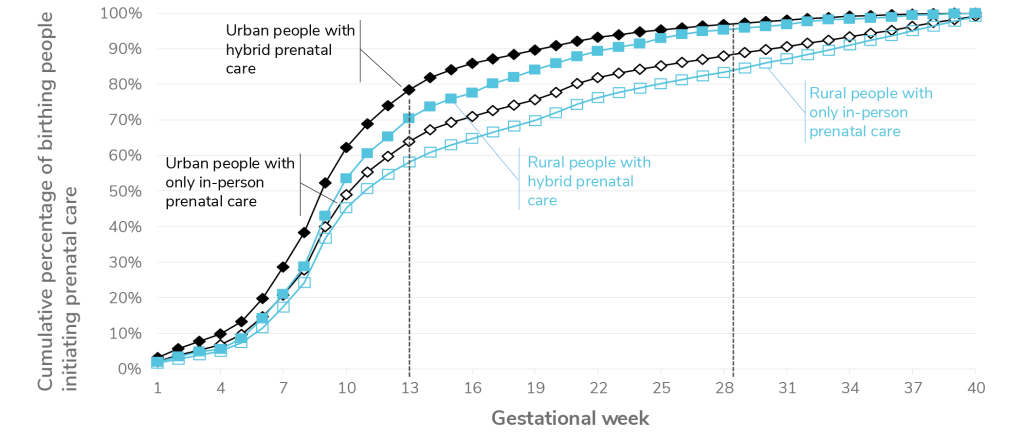

Analysis of racial disparities and geographic residence uncovered the same patterns regarding telehealth uptake and the timeliness of prenatal care initiation. Telehealth users were more likely to receive prenatal care in the first and second trimesters than those relying solely on in-person visits, regardless of race. Among those with only in-person care, fewer rural residents began care in the first trimester compared to urban residents. However, this residential disparity diminished for those using telehealth.

A line graph labeled “Urban versus rural prenatal care initiation.” The x-axis graphically displays gestational weeks from 1 to 40 in increments of 3 and the y-axis the cumulative percentage of birthing people in the United States initiating perinatal care from 0% to 100% in increments of 10%. The first line of urban people with hybrid care was the highest at 13 weeks compared with the rural people with hybrid prenatal care (the second line) but were similar by 28 weeks on to delivery. The third line of urban people with only in-person prenatal care was slightly higher than in rural people with only in-person prenatal care.

Selected Publications & Presentations

Hung, P., Granger, M., Boghossian, N., Yu, J., Harrison, S., Liu, J., Campbell, B. A., Cai, B., Liang, C., & Li, X. (2023). Dual barriers: Examining digital access and travel burdens to hospital maternity care access in the United States, 2020. The Milbank Quarterly, 1468-0009.12668. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0009.1266

Hung, P., Zhang, J., Chen, S., Harrison, S. E., Boghossian, N. S., & Li, X. (2024). A hidden crisis: postpartum readmissions for mental health and substance use disorders in rural and racial minority communities. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 231(4), e117–e129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2024.05.047

Odahowski, C. L., Hung, P., Campbell, B. A., Liu, J., Boghossian, N. S., Chatterjee, A., Shih, Y., Norregaard, C., Cai, B., & Li, X. (2024). Rural-urban and racial differences in cesarean deliveries before and during the COVID-19 pandemic in South Carolina. Midwifery, 136, 104075. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2024.104075